Students and families continuously inform improving Black students’ school experience.

West High School wanted to strengthen the school experience for Black students and their families. Instead of relying on educator-driven solutions, the school engaged students and families to design change. Focus groups became multi-faceted feedback loops that changed curricula and policy. Their example of vulnerability or holding “brave space” now serves as inspiration for other schools in the network.

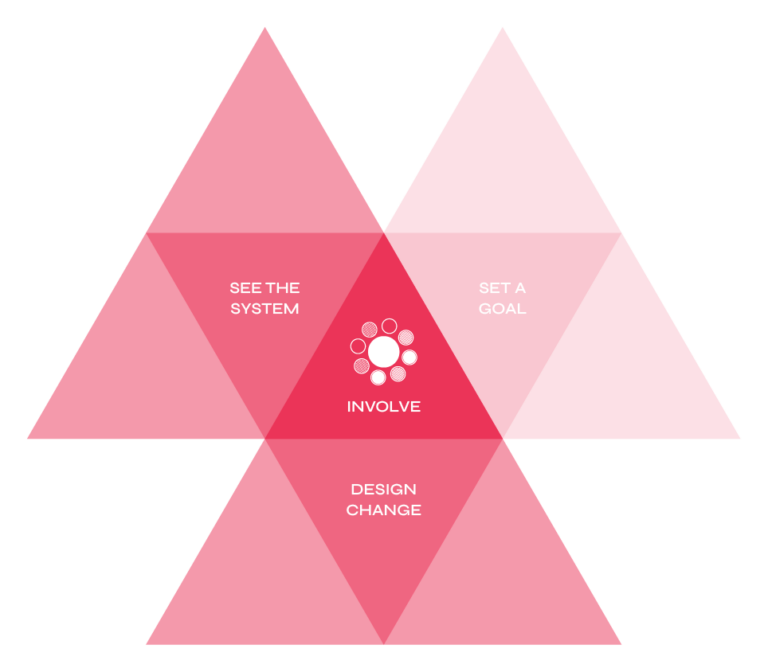

In this case study, students were involved in improvement efforts to see the system and design change. Learn more about the student-powered improvement framework here.

At West High School in Denver, Colorado, students and their families have been closely involved in efforts to understand and improve the school experience for Black students and their families. Part of the district’s College Ready on Track Networked Improvement, West High School spent a year testing and strengthening ways to involve students and families in their improvement efforts. Their example now serves as inspiration for other schools in the network.

Be human-centered is a key principle of improvement that drives the work at West High School. According to one assistant principal, “The focus of our school community is to serve our students and families. Therefore, it is imperative for their voices to drive the decisions and changes we make in our school.”

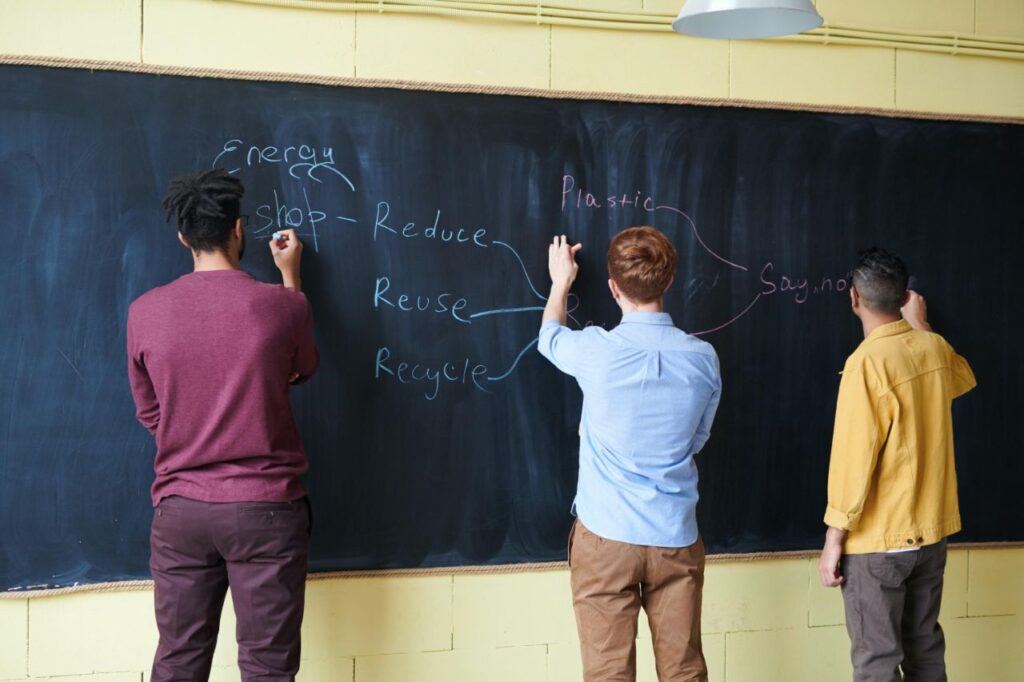

The design team at West High School began by designing focus groups for Black students and their families, to more deeply understand those groups’ experiences and perspectives. Over the year, the focus groups grew into multi-faceted feedback loops where students and families were repeatedly involved in helping to see the system, identify and shape change ideas, and determine direction.

One of the early lessons the team learned was about expanding how they identified who to involve. Initial outreach was to students and families who were coded as Black/African American in the district database. The team quickly realized that this demographic information left out all of those who might identify as Black/African American but were coded as biracial or multiracial. The team responded to this learning with new outreach.

The team also used rapid cycles of improvement to test and change the protocol they used with students and families. For example, their introduction to shared spaces (virtual or in-person) now includes a recognition of racism and power and the system’s failure to serve Black students and families. They also added the concept of “warm transfer” — a personal connection and transition into the space. For example, someone from the team might text or call a student or family member to walk them through how to join the virtual space and stay with them until they settle in.

From student and family focus groups, change ideas emerged including the creation of three new classes: ethnic studies, personal financial studies, and sociology (informally called the “Black Lives Matter” class). Once these classes began, students gave regular feedback about what was working and not working which led to ongoing changes.

Focus groups have become “360-degree communication in cycles and community action sessions,” said Derek Pike, Assistant Principal. He continued, “We bring people back as often as possible to tell us thumbs up, thumbs down, did we miss the mark.”

The student and family partnerships at West High School have become an inspiration and model to other schools in the network, says John Albright, Student Engagement Director and Project Director for the College Ready On Track Networked Improvement Community. Next year, more schools in the network will deepen their student and family partnerships using lessons learned from West High School.

By creating feedback loops, rather than one-time listening sessions, students and families have a deeper level of involvement. And, it is not only about deep listening; involvement now means everything from feedback to action.

The team at West High School has learned a number of lessons about creating what they call “brave space” for authentic student and family partnerships. Labeling power dynamics, acknowledging racism and historic harm, and focusing on warm transfer into the group are just a few of the many things described in their story and reflected in the focus group protocol [hyperlink]. Promoting vulnerability among all involved is an important component of brave space. Creating brave space also means that leaders/facilitators are on their own personal learning journeys about race, power, and privilege. “We must examine who we are and how we show up,” said Derek Pike.

From the beginning, the team at West High School prioritized the involvement of both students and their families. More than 40 family members who identify as Black, including 24 students, participated in one or more of the ongoing engagement opportunities. One staff member spoke to the power of partnering with both students and families, “[Through this engagement] we have come to that middle ground where we all understand each other and are better able to tolerate each other and live in harmony and as one. To have a beautiful school.”

The team at West High School strives to bring back students and families as often as possible. By creating feedback loops, rather than one-time listening sessions, students and families have a deeper level of involvement. And, it is not only about deep listening; involvement now means everything from feedback to action. To culminate the success of the ongoing partnership, the team recently held a celebration for students and families who have been involved.

According to Rhianna Burroughs, Assistant Superintendent, “Our response to feedback has resulted in changes this year to improve the student experience, but the journey has just begun. This is an iterative process where student and family voices have to consistently be heard.”