Students provide feedback on student-led assessments.

Current educational systems put very little power into the hands of students. Battelle for Kids wanted to change that by enlisting help from students who traditionally were not well served by education systems. Surprising insights resulted from the collaboration of students and teachers, including the development of a new, student-designed assessment rubric.

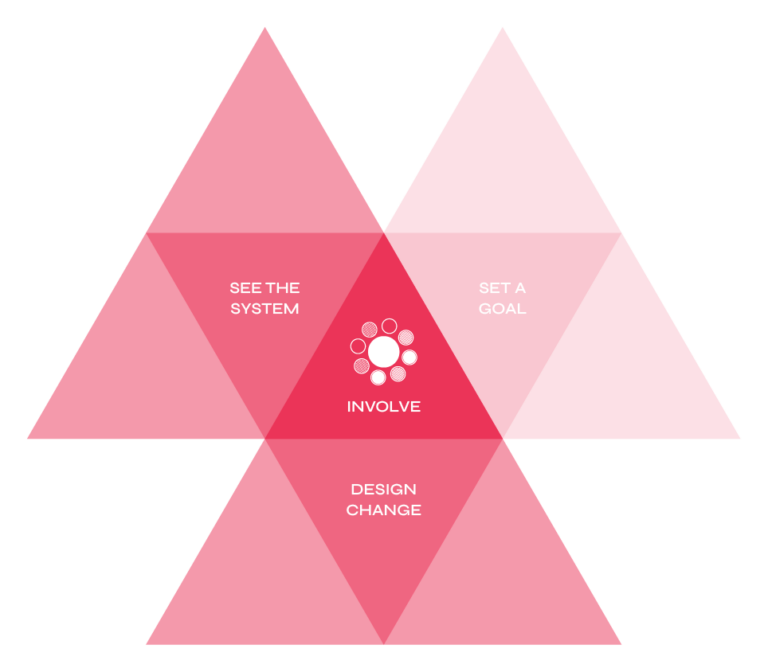

In this case study, students were involved in improvement efforts to see the system and design change. Learn more about the framework intersections here.

At Battelle for Kids, adolescent students participated in convenings of the Virginia Student-Led Assessment Networked Improvement Community (VA NIC) in multiple ways. From defining the problem to brainstorming change ideas, students provided feedback and contributed ideas at network convenings.

Network leaders at Battelle for Kids are well aware that the entire education system is “created by adults but done to kids.” By power mapping the current system, they saw how little power students had in school. “Students are key to redefining success; they are the users of our system,” said Shannon King, Chief Innovation Officer at Battelle for Kids.

The VA NIC set an ambitious AIM: to have 10,000 students across their districts engage in student-led assessments. They knew that student experiences and perspectives were critical to their success and so, from the beginning, they included students in each network convening.

The adults in the network agreed that they needed to hear from students who traditionally had little to no voice in the system. Teachers personally recruited a small, diverse group of students for each convening; focusing on those who the system had not served. Different students were recruited from the nearest locations to each convening. Students met with their teachers ahead of the convening to make sure they understood what to expect.

Each convening began with a grounding activity to build trust and an inclusive environment. To scaffold student entry into the predominantly adult space, students stayed together for this activity. For example, individuals in small groups shared what had been happening in their lives and compared their story to a movie, television show, or book.

Throughout each convening, intentional protocols were used to involve students in activities with adults. Examples include:

Student perspectives often led to surprising new insights for adults. For example, some students shared their experience that detailed rubrics could feel too constraining (one student called overly-specific rubrics “the death of autonomy”). This insight led to deeper conversations about the student view versus teacher view of rubrics. They ended up creating two versions of assessment rubrics; one that was student-friendly and another that teachers could use more specifically for scoring. The experience and perspectives students shared were critical to this change.

Student involvement had a fundamental impact on the direction of the network. “Students helped transform our thinking about assessments. They helped adults change the purpose of assessments and the communication and messaging around assessments. They taught us to be straight with them,” said King.

“Our focus is on the kids falling through the cracks. We are looking at our black and brown kids as they are the knowers of the why,” said Shannon King. Teachers who were responsible for recruiting students were asked, “not to pick the kids who came straight to their mind or who would usually volunteer. We asked them to find the students with attendance issues, behavior records, English language learners, students with special needs,” said King. Most teachers in the network leaned into this recruitment approach without hesitating.

Convening organizers knew that bringing students to convenings meant being even more intentional about the environment they were creating; everything from establishing norms to having fun. “We need to support the psychological safety of students. This takes time. We have to establish norms and keep them alive for everyone” said Shannon King, Chief Innovation Officer at Battelle for Kids.

Strategies included: