Students “stress test” educators’ change ideas about college access.

Across a network of California high schools, traditional ways of communicating with families weren’t working. Automated calls from the school, in particular, didn’t seem effective.

School staff looked to their network of student consultants for help. By asking students about modes of communication that worked for their families, they gained deep insights that led to the design of a new, two-pronged communication approach that included personal followup calls.

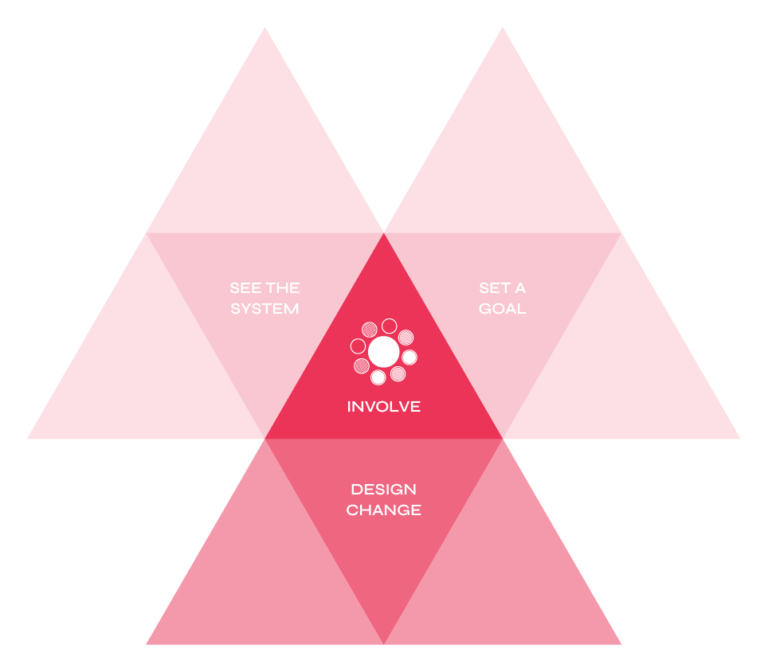

In this case study, students are involved in improvement efforts to design change. Learn more about the student-powered improvement framework here.

During convenings of the High Tech High College Access Network, CARPE design network, members always “design students in.” That means that they intentionally and carefully create structures for student involvement. One way this looks is that students serve as “change idea consultants;” adults present ideas and students provide authentic feedback.

“We want to provide consistent routines to get feedback and involve students that is not the historic pattern of tokenizing students,” said Rodrigo Arancibia from High Tech High. Regularly including students affirms their importance as stakeholders in the design process as well as the resulting changes.

“When we design agendas, we think about where in the convening space it would be beneficial for students to be engaged in the conversations,” said Arancibia. In other words, organizers are mindful to create spaces in convenings where students will feel more comfortable and have opportunities to make meaningful contributions. In addition, they are testing design time with students to gather direct feedback and ideas while the agenda and activities are in development.

Before students enter a convening space with adults, they first meet together with a network adult to build relationships and walk through what will happen in the convening. They have found this welcome time to be a valuable component of successful student involvement. “We prep the adults with questions to ask students and then prep the students to know some of the questions they might hear from adults,” explained Arancibia.

Usually, each school invites a few students (never just one!) to a convening. Leaders are careful to consider who to invite by considering the specific problem they are trying to solve. If their AIM, for example, is to improve high school completion for Latino males, then the students who will be included are Latino males who are at risk of not completing their degree.

One role students play at convenings is to be “consultants” by providing honest feedback on change ideas. Adults “pitch” a change idea related to supporting college decisions and then ask students questions like: What do you think of this? Would this work for you? How would your friends react to this? Using the liberatory design principle of “share, don’t sell” an idea, they also ask students to stress test the idea: Why wouldn’t this work? What would get in this way? Why wouldn’t your friends want to do this?

As an example, students were consultants on ideas related to communication with families. Educators asked three students, “Does your family want an automated call or a personal call from the school?” Students’ answers varied. One student described wanting a personalized call in order to ask follow-up questions. Another student said her mother was too busy for anything except automated calls.

These student insights led to a new approach to the communications system. Instead of choosing and building one approach, the team created a two-pronged approach where all families received automated calls and some would receive a follow-up personal call.

Student involvement is a regular part of network convenings, which allows both adults and students to practice trusting each other’s ideas and input. Further, adults and students are engaged in a process of inquiry about adults’ ideas; students’ role is not to validate what adults propose.

Carefully consider which students you are targeting in your AIM and be sure that those are the students who you prioritize including. For example, if your AIM is to improve high school completion for Latino males, then the students who most need to be included are Latino males who are at risk of not completing their degree.

This vignette illustrated several ways the network intentionally prepares to partner with students. First, students aren’t just invited for the sake of having them there. Rather, the agenda is carefully constructed and students are included in activities and spaces where there can be an authentic partnership. Second, students have time together before they enter space with adults to understand what is going to happen and what their role can be.