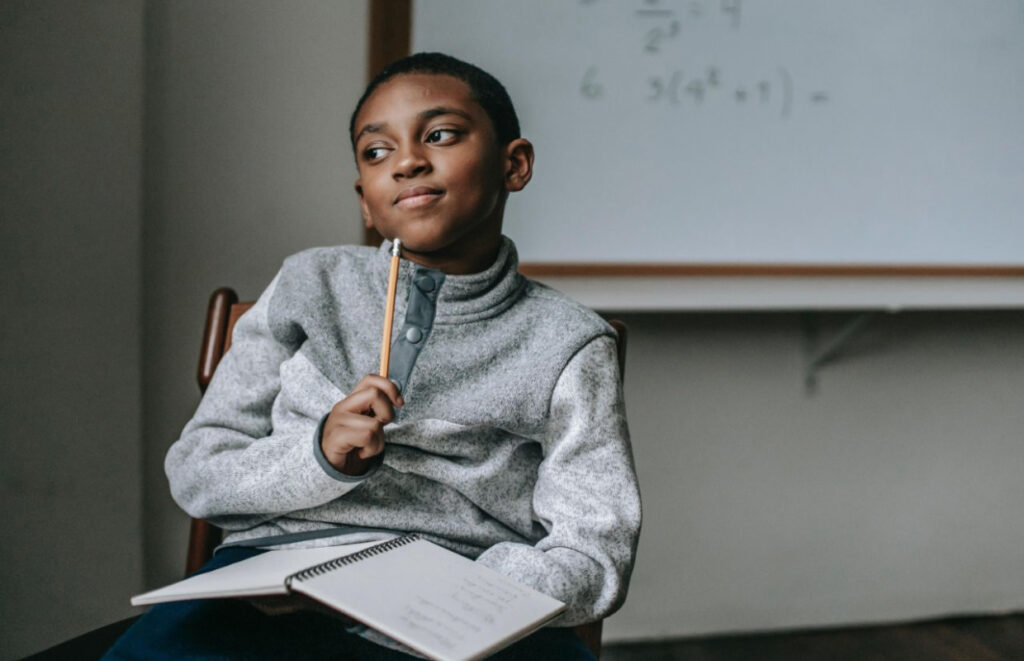

Students become partners in re-imagining school culture.

A school climate and culture team could not move the needle on improving this critical aspect of their school. Staff realized they needed to create school culture with students rather than for them. By collaborating with historically marginalized youth, they focused on authentic relationship building, the development of a student-led culture and climate committee, and the creation of intervention peer mentors.

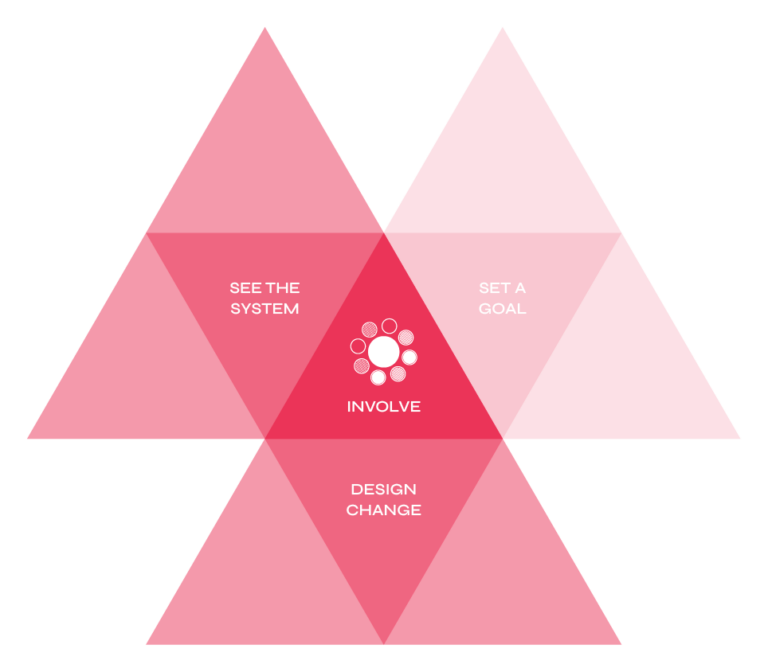

In this case study, students were involved in improvement efforts to see the system and design change. Learn more about the student-powered improvement framework here.

A school climate and culture team pivoted their approach to improvement by inviting students to be full members of their team. They held a multi-day retreat with adults and students for a deep dive into seeing the system and then to “reimagine” together.

“Everything shifted once students were involved,” said an organizer. When their improvement team only included adults, they looked at data, picked an intervention, and tried it out. But the data they considered were limited—things like absentee data and single survey items. According to a team member, the data didn’t include the lived experiences of students and families, and the adult team “hit a wall” without it. They knew that they needed students.

To truly examine school climate and culture, students needed to be part of the team. A group of youth who were students at the school and also members of Californians for Justice helped push the school administration towards student + adult co-design. “It was students who really pushed for this,” said an organizer. The students told the administration, “This is what we are seeing in our school; let’s try to work on this together.”

Their work began with a multi-day retreat for adults and students. Over seven students and student alumni were invited along with ten adults including teachers, counselors, administrators, and a community schools manager. They knew that they needed to engage with students who were historically marginalized by the system and whose lived experiences could authentically inform change, so they focused on students with discipline issues.

Together, students and adults worked to see the system and then reimagine it. They conducted empathy interviews with each other to add to the more traditional data. Students asked adults questions like, “Talk to us about an impactful journey with the student you supported this past semester.” Adults asked empathy interview questions such as, “Share a time when you felt misjudged or underestimated by a teacher, staff, or peer based on your race or some part of your identity. What support might have helped prevent this?”

These new data helped the team see where things were working and where things needed to be reimagined. The school created an additional student culture and climate committee that was student-led. The students met separately and came together with school staff for the larger culture and climate meetings. Staff tried more empathy interviews as an intervention that semester. They also made adjustments on several interventions based on what students and staff decided—e.g., increase the frequency of check-ins administrators had with students who had discipline issues—so they would build stronger relationships and provide more support to catch those students up in their academics. They also decided to start a student-led intervention using peer mentors for students who were having discipline issues.

After this work, the adults on the team, “had an exhalation of ‘why haven’t we done this before?’” and agreed that whatever students wanted to do, they would do it.

The team knew that they needed to engage with students who were currently and historically marginalized by the system, and whose lived experiences could authentically inform change, so they focused on students who had discipline issues.

In the school where this story took place, students had been invited to tables with adults before. The difference, said Geordee Mae Corpuz, Strategy Director for Californians for Justice, was that, “Students were just there. The space wasn’t designed for them. We hadn’t actually created space for them.” Together with students, the administration decided to more intentionally create space for students and young people to work together.

An important principle of setting up mutual space was for the students and adults to hold the culture of the space together. “We very intentionally built a retreat space where students could be. This took time and intentionality,” said Geordee Mae Corpuz. “The tension is that people still want to meet outcomes quickly, but this requires building relationships and building trust. It takes a lot of time and patience and doesn’t necessarily achieve outcomes right away.”

This vignette highlights how students themselves were key advocates for ensuring that adult + student partnership began, by repeatedly asking to have more voice at the change table. The youth leadership development program with Californians for Justice helps build the capacity of youth to organize and advocate for change. Throughout the experience, youth learn about how schools work, why they work that way, and how plans and interventions develop. This learning helps students see the whole picture and, thus, engage directly in conversations about the systems. “It is important for students to understand the nuance of the systems. What is it? Why does it hold power? Who are the players?” said an organizer.