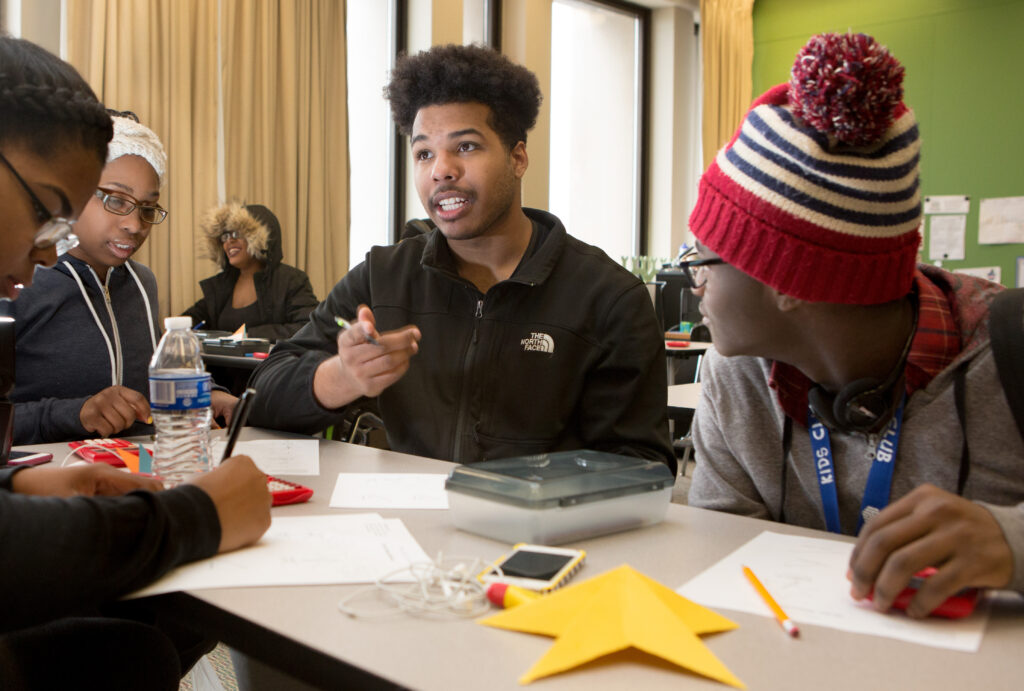

A student advisory board influenced curriculum and developed student advocates

Students who participated in the Center for Supportive Schools (CSS) saw a need for the programs to be informed by youth. With support from CSS, students created a Let Students Lead Advisory Board to provide youth-led guidance for programs and curriculum. As youth designed new events and outreach programs for their peers, they also grew their leadership and advocacy skills.

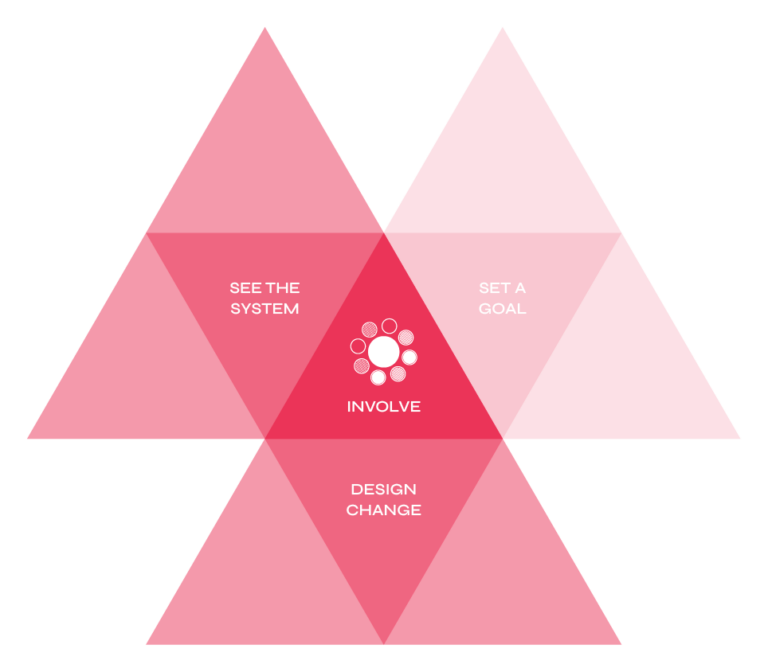

In this case study, students were involved in improvement efforts to see the system and design change. Learn more about the student-powered improvement framework here.

The Let Students Lead Youth Advisory Board is a yearlong experience for youth to improve the programs and services offered to schools by the intermediary organization, Center for Supportive Schools (CSS). Each year, about a dozen students from high schools in multiple states make changes to curriculum, create social media content, and plan events and outreach for the CSS community.

Let Students Lead Advisory Board was inspired by the desire to design programs and strategies with youth, rather than for youth. The idea for the Board came from youth themselves. Two students who were involved with CSS in high school wanted to create more opportunities for students to voice their opinions and ideas in ways that create effective change. CSS staff listened to their ideas and hired them to lead the Board’s creation.

The Board was also designed to grow the knowledge, skills, and urgency within youth to become lifelong advocates. The opportunity puts students in leadership positions to aid their development during adolescence.

The idea of a Let Youth Lead Advisory Board came from two students, Janikaa Jackson and Kiana Dixon, who were deeply involved with CSS programs in high school. After high school graduation, the two women were hired by CSS to lead the design and implementation of the Advisory Board. While attending college, Janikaa and Kiana led Advisory Board recruitment, scheduled and facilitated all of the advisory meetings, maintained communication with youth five days a week, and built programming.

“It wasn’t hard work, but it took a lot of work,” said Janikaa. Kiana added, “Our role with CSS in high school gave us a deep foundation to even have this idea. To actually create something like this from scratch was a lot of work. We enjoyed doing it, but it was eye-opening how much work we had to put in so that the whole thing made sense.”

In the design phase, the team thought deeply about what would make the Advisory Board a meaningful experience and result in real change. In addition to a $500 stipend for participation, their recruitment outreach emphasized that this was an opportunity to:

In the first year, thirteen youth were recruited from schools across New York, New Jersey, and North Carolina. Organizers looked for a diverse group of young people who had already participated in at least one CSS program that the advisory board would influence: Peer Group Connection (PGC) that supports transitions into middle or high school, or Teen Prevention Education Program (Teen PEP), a comprehensive sexual health program. Their outreach strategy was to send emails to every staff member in the CSS network. They also reached out teachers who had participated in CSS programming for student recruitment. Organizers also publicized the opportunity through social media.

The group met together on Zoom once a month across the school year. Each young person was also part of a subcommittee (curriculum, outreach, or social media) that met more frequently. A daily group chat was used for ongoing communication and connection.

Advisory meetings usually had three components:

One of the culminating activities created and facilitated by youth was called Community Exhale. Teachers and students came together to connect about their lives–both the highs and the lows–as a chance to build connections and focus on relationships during difficult times. With this activity, students were modeling for adults how to center relationships and attend to mental health.

A priority for Let Students Lead was to create space for students to speak their truth. “A lot of times, adults don’t take students’ perspectives seriously,” said Janikaa Jackson, “This space is for youth to speak their truth and have it legitimized.” For example, youth had a clear desire to address mental health issues they experienced and witnessed among their peers, issues they felt were often overlooked or minimized by adults.

Meetings were carefully planned so that there was time to deepen relationships, build trust, and share experiences. “We didn’t just jump into meetings. There was always time to debrief, take a step back, and check in before we got into the agenda,” explained Kiana Dixon. Some of the specific strategies for creating space where students could be themselves included:

Finally, the adults recognized the importance of reciprocal sharing. They did not just expect students to share, but they themselves opened up honestly about the highs and lows in their own lives. “We stayed true to ourselves. If you have that mentality, others open up to you,” said Dixon.

The CSS team knew there was work that adults needed to engage in to ensure a two-way partnership. For example, they offered the adults strategies for responding to students’ feedback. A strategy called “ice cream sandwich” offered a pattern of good comment/honest feedback/good comment which “helped set up teacher/student conversation so that students gave honest feedback and adults were prepared to respond in a way where students felt heard.”

Another important value that helped address power dynamics between youth and adults was reciprocal sharing. “Adults have to have a certain level of openness,” explained Dixon. “In other words, teachers sharing about their own lives outside of school and acknowledging the human connection with students as they express similar stresses, highs, and lows.”

As advisors, students were provided with time and support to build skills they needed for their work. For example, they learned about and practiced: