Student voice has become embedded in a school’s culture.

At Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Early College, the school worked to shift its culture toward centering students, thus decentering adult power. They used various methods to gather student feedback across the school. Putting students first has led to positive changes in school policies, curriculum, equitable grading practices, and overall school culture.

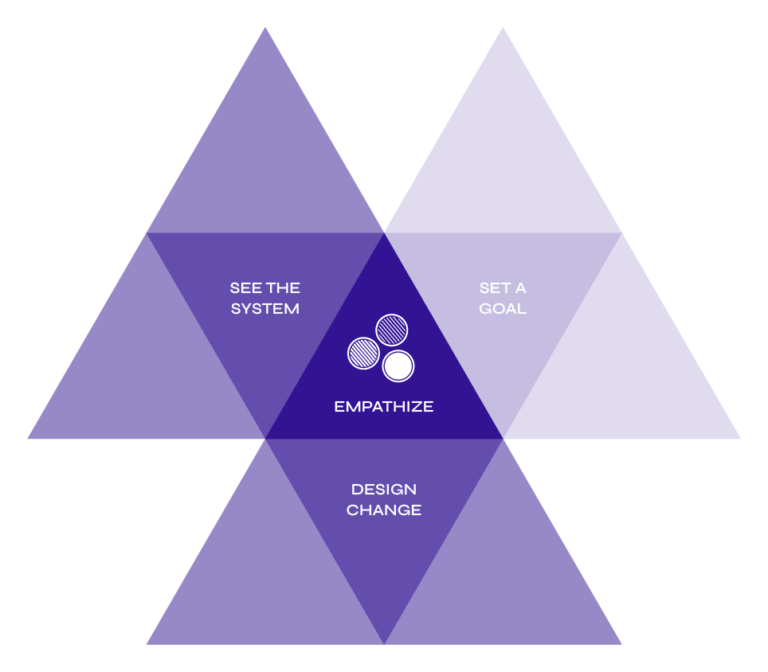

In this case study, adults empathize with students in order to see the system and design change. Learn more about the student-powered improvement framework here.

Student voice is central to how Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Early College in Denver, Colorado operates. Through surveys, one-on-one interviews, and small-group feedback sessions, student voice shapes what happens in classrooms and across the school, from curriculum decisions to policies.

Staff at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Early College know that students’ perspectives are critical to effective and authentic change. They want to shift away from education systems where adults hold all the power to a culture where student voice drives change.

Any time we want to try something new, we run it by students first,” said CJ Smith, Assistant Principal. He went on to describe frequent and varied opportunities for student feedback, such as:

Policy feedback. When remote learning continued to be a reality due to COVID-19, some adults wanted to require all students to turn their cameras on in class. Instead of instituting this policy, they took the issue to students through an online survey. When asked, “Do you want to see your peers during class?” the vast majority of students said “no.” The adults listened and the policy was not instituted.

Curriculum choices. Students were asked to give feedback and ideas about the content of their U.S. History courses. Students expressed that they wanted to see themselves in the curriculum. They wanted to know more than just the tragic loss of life and liberty that Black students experienced. They wanted to learn about the honor and prestige people of color have brought to our country, our society, and our world.

Equitable grading practice. As part of the College Ready on Track Networked Improvement Network in Denver, the school is focusing on equitable grading practices. Fourteen teachers began using new grading practices that they learned through a book study. Students were regularly asked to provide feedback about their experiences in these classrooms. One data point showed that more than 90 percent of students said the new feedback was useful, a critical piece of information to encourage the team to deepen their practice.

Root cause analysis. To “see the system” around issues such as attendance and engagement, staff reached out to students. Questions like, “Why do you come to school,” “What are your post-secondary goals?” and “What are you struggling with the most right now?” helped staff identify root causes of problems in the system and begin to focus improvement efforts.

As described in the examples above, the methodology for student feedback also varies. From school-wide surveys to individual conversations, the takeaway from their work is to turn to students frequently and in multiple ways.

In this example, adults not only turned to students about a school policy, but deferred to students’ strong preference for cameras to be optional during online learning. This decision was made despite how many adults felt strongly that they should be on. In this case, adults took the time to develop true empathy for students’ experience with cameras and online learning.

Moving towards a culture of student voice first required mindset shifts among the adults. “First, the adults had to allow ourselves to be vulnerable,” said CJ Smith, Assistant Principal at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Early College. “We have to be willing to say there are things we don’t know.”

Scaffolding supports also meant starting small and going against the popular notion in education that all good ideas should start at scale. “It’s okay to start by talking to five or six students or a few students from each grade level,” said Smith.

The goal is to create space where students can be their most authentic selves, said Smith. It is important to ground in existing relationship or create space to build relationship with someone new. “I want students to feel comfortable so I need to figure out what they need from me first,” said Smith. One strategy is for the adult to share something first.

Creating safer spaces also means being upfront and realistic about what might happen with their suggestions. “I tell students that I am in a position of power, but I can’t promise change. I say that what they tell me will be meaningful to me, but I can’t promise them anything.”